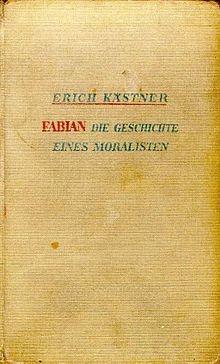

Count Leo Tolstoy is one of the most revered prose writers in Russian history. The significance of his work cannot be overestimated. The author has given a special place in his work to military subjects, and the collection "Sevastopol Stories" is a vivid representative of this genre. "Sevastopol Stories" was published in 1855. A feature of these essays is the fact that the writer himself was a participant in the described military operations, and, one might say, tried on the role of a war correspondent. The collection was written in less than a year, and all this time Tolstoy was in the service, which allowed him to convey with surprising accuracy the main events of those months. The plot is completely realistic, and that’s exactly what the short retelling from the Literaguru team conveys.

Sevastopol in the month of December

The narrator arrives in besieged Sevastopol and describes his impressions, combining descriptions of the most seemingly everyday things, and listing the horrors of war that pervade everywhere - a mixture of "city life and a dirty bivouac."

He enters the Assembly Hall, which houses a hospital for wounded soldiers. Each soldier describes his wound in different ways - someone did not feel pain, because he didn’t notice the wound in the heat of battle, and was hungry for discharge, and a dying man, already “smelling of a dead body”, did not see and understand anything. A woman who was carrying lunch to her husband lost a leg knee-deep from a shell. A little further, the author falls into the operating room, which he describes as "a war in its present expression."

After the hospital, the narrator finds himself in a sharply contrasting place with the hospital - a tavern where sailors and officers tell different stories to each other. For example, one young officer serving on the most dangerous, fourth bastion, swaggers, pretending that he is most concerned about dirt and bad weather. On the way to the fourth bastion, there are fewer non-military people, and more and more exhausted soldiers, including wounded on a stretcher. Soldiers, long accustomed to the rumble of gunfire, calmly wonder where the next shell will fall, and the artillery officer, seeing a serious wound to one of the soldiers, calmly comments: “This is every day seven or eight people.”

Sevastopol in May

The author discusses the aimlessness of bloodshed, which neither weapons nor diplomacy can solve. He considers it true if only one soldier fought on each side - one would defend the city and the other would besiege, saying that it was “more logical because it was more humane”.

The reader gets acquainted with headquarters captain Mikhailov, ugly and awkward, but giving the impression of a man "a little taller" than an ordinary infantry officer. He reflects on his life before the war and finds his former circle of communication much more sophisticated than the current one, remembering his friend-lancer and his wife Natasha, who is looking forward to news from the front about Mikhailov’s heroism. He is immersed in the sweet dreams of how to get promoted, dreams of being included in the higher circles. The headquarters captain is embarrassed by his current comrades, the captains of his regiment, Suslikov and Obzhogov, wanting to approach the "aristocrats" walking along the pier. He cannot force himself to do this, but, in the end, joins them. It turns out that each of this group considers someone “a great aristocrat” than he himself, everyone is full of vanity. For the sake of a joke, Prince Galtsin takes Mikhailov's arm during a walk, believing that nothing will bring him more pleasure. But after some time they stop talking with him, and the captain goes to his home, where he remembers that he volunteered to go to the bastion instead of a sick officer, wondering if they will kill him, or simply injure him. In the end, Mikhailov convinces himself that he did the right thing, and in any case he will be awarded.

At this time, the "aristocrats" were talking to Adjutant Kalugin, but they were doing so without past mannerisms. However, this lasts only until the officer appears with a message to the general, whose presence they demonstratively do not notice. Kalugin informs his comrades that they are faced with a “hot deal”, Baron Pest and Praskukhin are sent to the bastion. Galtsin also volunteers to go on a sortie, knowing in his soul that he will not go anywhere, and Kalugin dissuades him, while realizing that he is afraid to go. After some time, Kalugin himself leaves for the bastion, and Galtsin interrogates wounded soldiers on the street, and at first is indignant at the fact that they "just" leave the battlefield, and then begins to be ashamed of his behavior and Lieutenant Nepshitshetsky, screaming at the wounded.

Meanwhile, Kalugin, showing pretense of courage, first drives the tired soldiers in their places, and then goes to the bastion, not bending down under the bullets, and sincerely gets upset when the bombs fall too far from him, but falls in fear to the ground when next to him the shell explodes. He is amazed at the “cowardice” of the battery commander, a true brave man, half a year after living on the bastion when he refuses to accompany him. Kalugin, driven by vanity, does not see the difference between the time spent by the captain on the battery and his few hours. Meanwhile, Praskukhin arrives at the redoubt, on which Mikhailov served, with instructions from the general to go to the reserve. On the way, they meet Kalugin, bravely walking along the trench, again feeling brave, however, not daring to go on the attack, not considering himself “cannon fodder”. But the adjutant finds the cadet Pest, who tells the story of how he stabbed the Frenchman, embellishing it beyond recognition.

Kalugin, returning home, dreams that his "heroism" on the bastion deserves a golden saber. An unexpected bomb kills Praskukhin and easily injures Mikhailov in the head. The headquarters captain refuses to go to the dressing, and wants to find out if Praskukhin is alive, considering it "his duty." After ascertaining the death of a comrade, he catches up with his battalion.

The next evening, Kalugin with Galtsin and “some” colonel walk along the boulevard and talk about yesterday. The adjutant argues with the colonel about who was at a more dangerous frontier, to which the second is sincerely surprised that he did not die, because four hundred people died from his regiment. Having met the wounded Mikhailov, they behave with him as arrogantly and scornfully as before. The story ends with a description of the battlefield, where under the white flags the parties disassemble the bodies of the dead, and ordinary people, Russians and French, stand together, talk and laugh, despite yesterday’s battle.

Sevastopol in August 1855

The author introduces us to Mikhail Kozeltsov, a lieutenant who was injured in the head in battle but recovered and returning to his regiment, whose exact location, however, was unknown to the officer: the only thing he learns from a soldier from his company is that his regiment transferred from Sevastopol. The lieutenant is a “remarkable officer,” the author describes him as a talented person, with a good mind, good speaking and writing, with a strong pride that makes him “excel or be destroyed.”

When Kozeltsov’s transport arrives at the station, it is crowded with people who are waiting for horses that are no longer at the station. There he meets his younger brother, Volodya, who was supposed to serve in the guard in St. Petersburg, but was sent - at his request - to the front, in the footsteps of his brother. Volodya is a young man of 17 years old, attractive in appearance, educated, and a little shy of his brother, but treating him like a hero. After the conversation, the elder Kozeltsov invites his brother to immediately go to Sevastopol, to which Volodya agrees, externally showing determination, but hesitating inside, however, believing that it is better “even with his brother”. However, he does not leave the room for a quarter of an hour, and when the lieutenant goes to check Volodya, he seems embarrassed and says that he owes one officer eight rubles. The elder Kozeltsov pays his brother’s debt, spending the last money, and together they go to Sevastopol. Volodya feels offended that Mikhail chastised him for gambling, and even paid off his debt “from the last money”. But on the road, his thoughts turn into a more dreamy channel, where he imagines how he fights with his brother “shoulder to shoulder”, about how he dies in battle, and he is buried with Mikhail.

Upon arrival in Sevastopol, the brothers are sent to the regiment’s wagon train to find out the exact location of the regiment and division. There they talk with a convoy officer who counts the regimental commander’s money in a booth. Also, no one understands Volodya, who went to war voluntarily, although he had the opportunity to serve "in a warm place." Upon learning that Volodya’s battery is located on Ship, Mikhail offers his brother to spend the night in the Nikolaev barracks, but he will need to go to his place of service. Volodya wants to go to his brother for a battery, but Kozeltsov Sr. refuses him. On the way, they visit Michael’s friend in the hospital, but he doesn’t recognize anyone, he is tormented and awaits death as deliverance.

Mikhail sends his batman to Volodya’s escort to his battery, where Kozeltsov Jr. is offered to spend the night on the bed of the on-duty staff captain. A junker is already sleeping on it, but Volodya is in the rank of ensign, and therefore the younger in rank must go to sleep in the yard.

Volodya cannot sleep for a long time, in his thoughts the horrors of war and what he saw in the hospital. Only after prayer does Kozeltsov Jr. fall asleep.

Michael arrives at the location of his battery and there goes to the regiment commander to report on arrival. It turns out to be Batrishchev - a military comrade of Kozeltsov Sr., promoted in rank. He talks coldly with Mikhail, laments the lieutenant’s long absence and gives him a company under his command. Coming out of the colonel, Kozeltsov complains about the observance of subordination, and goes to the location of his company, where he is joyfully greeted by both soldiers and officers.

Volodya, on his battery, was also well received, the officers treat him like a son, instructing and teaching, and Kozeltsov Jr. himself asks them with interest about battery affairs and shares news from the capital. He also gets acquainted with the cunker Vlang - the very one in whose place he slept at night. After lunch, a report comes of the necessary reinforcements, and Volodya, drawing lots, with Vlang goes to the mortar battery. Volodya is studying the Guide to Artillery Shooting, but it turns out to be useless in a real battle - the shooting is random, and during the battle Volodya almost dies.

Kozeltsov, Jr. gets acquainted with Melnikov, who is not at all afraid of bombs, and despite warnings, gets out of the dugout and is under fire all day. He feels brave and proud to perform his duties well.

The next morning, an unexpected attack occurs on the battery of Michael, who is sleeping dead after a stormy night. The first thought that came to his head was the idea that he might look like a coward, so he grabs a saber and runs into battle with his soldiers, inspiring them. He is injured in the chest, and as he dies, he asks the priest whether the Russians have recaptured their positions, to which the priest is hiding news from Michael that the French flag is already flying on the Makhalov Kurgan. Calmed down, Kozeltsov Sr. dies, wishing his brother the same "good" death.

However, the French attack overtakes Volodya in the dugout. Seeing the cowardice of Vlang, he does not want to be like him, so he actively and boldly commands his people. But the French bypass the position from the flank, and Kozeltsov Jr. does not have time to escape, dying on the battery. Makhalov barrow captured by the French.

Surviving soldiers with a battery plunged onto the ship and moved to a safer part of the city. The rescued Vlang mourns for Volodya, who became close to him, while other soldiers say that the French will soon be driven out of the city.

You can agree on everything.

You can agree on everything.